During slavery, there was little if any dignity for African-Americans – even in death. It was against the law for African-Americans to assemble or meet as a group, so slaves were often buried without ceremony, on non-crop producing land, in graves that were often unmarked. With the end of slavery, African-Americans in the South were free to assemble, live as families, celebrate life and mourn death though segregation now stretched from birth past death; from the place you were born to where you could live, to your final resting place. For approximately 5,000 African-Americans, that final resting place was Evergreen Cemetery.

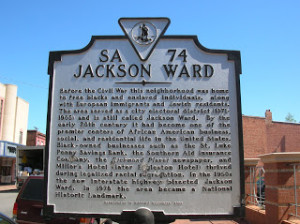

As early as 1891, just a 26 years after the end of the Civil War, when African Africans in Richmond, the former seat of the Confederacy, buried their loved ones and commemorated their lives with headstones, they did so in Evergreen Cemetery. Really four cemeteries on 59 acres— Evergreen, East End Cemetery, Oakwood Colored Section and the Colored Pauper’s cemetery— were private cemeteries maintained by the Evergreen Cemetery Association. These burial places served as the final resting place for many of Richmond’s prominent African American citizens. It is in Evergreen, designed to be the African American’s community’s equivalent of Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery which was only for whites, that Maggie L. Walker and John Mitchell, Jr., who I mentioned in last week’s post about Jackson Ward, are buried.

Evergreen Cemetery in Provenance

I learned about Evergreen Cemetery in my research for my novel, Provenance, when a prominent character’s death became a pivotal scene in the book. On his deathbed, my character, Hank Whitaker, reveals to his unsuspecting family that he is really a black man who has been passing for white. His mother-in-law, Charlotte, tries to quickly mitigate the effect that Hank’s news will have on her daughter and grandson. The following excerpts from Provenance is an example of one of the ways used Evergreen to convey how society used race and class to determine the worth of a human being.

If they were going to salvage anything, she would have to move fast. By tomorrow, Hank’s deathbed confession would be rumor. Within three days, the efficiency of gossip in Richmond society would ensure that Hank Whitaker’s passing was all people talked about. Charlotte was not about to wait for talk to turn to action – there were severe consequences for colored folks who tried to pass for white. She’d seen trees bearing the bodies of black men for doing a lot less than Hank had. “They will not take their vengeance out on Maggie and Lance, no matter what Hank did,” Charlotte vowed.

§

She looked at the piece of paper crumpled in her hand. She’d gotten the number of an undertaker from a colored nurse in the hospital’s segregated ward.

“Go to the hospital and get him tonight,” she instructed the undertaker after giving him the pertinent details.

“Bury him in Evergreen,” she said referring to the Negro cemetery in Richmond’s East End. She didn’t tell him Hank Whitaker was her daughter’s husband, she told them she was paying for the burial because his family couldn’t afford it. “We’re not having a service. I’ll come around tomorrow to pay whatever it costs.” With that, she had taken care of the inconvenient remains of Hank Whitaker.

§

She alone had presided over Hank’s burial. With the scent of freshly dug earth in the air, the two gravediggers lowered the plain pine coffin into the new grave.

“Are you sure you won’t be wantin’ a marker for the grave?” the undertaker asked her a second time. “Evergreen’s sixty acres, Mrs. Bennett. If you ever want to find this grave again—” Charlotte shook her head, no, before the man could finish.

“Then will you be sayin’ a few words before they close the grave?” he asked, hoping this woman was not as cold and heartless as she appeared. Again, Charlotte declined.

“Just cover him up,” she said. “Cover him up good.”

Evergreen Cemetery Today

Evergreen was founded and maintained by the families of the people who were buried there. Unlike the white cemeteries in Richmond, Evergreen received no public funds or support. As African-American families left the South and integration diminished the need for segregated facilities and services, sacred places like Evergreen soon fell into disrepair. Today Evergreen Cemetery is abandoned, overgrown and vandalized. Abandoned Virginia #22 – Evergreen Cemetery Richmond by Brian Sterowski, filmed in July of 2015, shows Evergreen as it is today.

Evergreen was founded and maintained by the families of the people who were buried there. Unlike the white cemeteries in Richmond, Evergreen received no public funds or support. As African-American families left the South and integration diminished the need for segregated facilities and services, sacred places like Evergreen soon fell into disrepair. Today Evergreen Cemetery is abandoned, overgrown and vandalized. Abandoned Virginia #22 – Evergreen Cemetery Richmond by Brian Sterowski, filmed in July of 2015, shows Evergreen as it is today.

A recent photo essay in The Nation, Reclaiming Black History, One Grave at a Time by Brian Palmer and Erin Hollaway Palmer, is a powerful statement on the years of official neglect that, along with the English ivy and other invasive plants, have swallowed the East End Cemetery of Evergreen Cemeteries. The history of prominent early 20th century African-Americans and World War II veterans buried there is now further obscured by the indignity of also having their graves buried. A BBC film by Colm O’ Molloy is about photographer, Brian Palmer, who is working to document the graves in East End Cemetery as a way to raise the awareness of this loss of history and heritage.

However bleak the current state of Evergreen Cemetery, there may still be a future to the past this historic site represents. Several historic and civic associations, as well as local college students and community volunteers, are working to save the history that Evergreen represents for all Americans. A video of Evergreen Cemetery Historic Marker Dedication by the National Park Service features magnificent images of Evergreen’s history and a glimpse of what its future could hold.

Here I Lay My Burdens Down: A History of the Black Cemeteries of Richmond, Virginia by Veronica Davis is the resource for more information about Evergreen Cemetery.

Evergreen was founded and maintained by the families of the people who were buried there. Unlike the white cemeteries in Richmond, Evergreen received no public funds or support. As African-American families left the South and integration diminished the need for segregated facilities and services, sacred places like Evergreen soon fell into disrepair. Today Evergreen Cemetery is abandoned, overgrown and vandalized.

Evergreen was founded and maintained by the families of the people who were buried there. Unlike the white cemeteries in Richmond, Evergreen received no public funds or support. As African-American families left the South and integration diminished the need for segregated facilities and services, sacred places like Evergreen soon fell into disrepair. Today Evergreen Cemetery is abandoned, overgrown and vandalized.

In Provenance, Jackson Ward is home to Mrs. Delora ‘Del’ Holder, a character that resonates with so many readers. She is the moral center of the book, a well of wisdom and humanity that sustains a family in their most difficult time. Del’s home and family in Jackson Ward are what sustained her. While Del is a fictional character, real places like Jackson Ward sustained people of color. In the relative safety of these segregated communities, though many were the target of racial violence, they nevertheless offered communal nurturing and concern that was not available elsewhere. They gave African-Americans an environment in which to exceed the potential others believed they did not have.

In Provenance, Jackson Ward is home to Mrs. Delora ‘Del’ Holder, a character that resonates with so many readers. She is the moral center of the book, a well of wisdom and humanity that sustains a family in their most difficult time. Del’s home and family in Jackson Ward are what sustained her. While Del is a fictional character, real places like Jackson Ward sustained people of color. In the relative safety of these segregated communities, though many were the target of racial violence, they nevertheless offered communal nurturing and concern that was not available elsewhere. They gave African-Americans an environment in which to exceed the potential others believed they did not have.