I have very mixed feelings about National African American History Month, also called Black History Month, which is why I haven’t added posts to my blog during February. Historian Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History suggested the week that became the month of February’s annual observance of important people and events in the history of the African diaspora. Since the history of African Americans has been the hidden and marginalized history of the United States of America, I believe there should be full integration of African Americans in American history. I wonder if giving the history of African Americans one month on the calendar and “American History” all year all the time further marginalizes the significant people, events, contributions, and sacrifices February is supposed to celebrate.

Some say take the month and really celebrate; others say you can’t, in just a month’s time, celebrate or even tell how America became America on the backs of people who still struggle for respect and a fair share of her riches. I raise these issues, though I don’t pretend to have the definitive answer to this historical equity dilemma. I choose to share what I know and what I find out about Black History in America—my history—throughout the year.

There is so much we don’t know about ourselves that even with one daily revelation, I doubt we’d ever run out of people, events, contributions and sacrifices to share. In just this past year, I wrote about Eugene Jacque Bullard, Maggie Lena Walker, Belle da Costa Greene, and important places like Richmond’s Jackson Ward and Evergreen Cemetery, just from the research I uncovered while writing my novel, Provenance.

For Veterans Day I wrote about the military prowess of African-Americans in America’s fight for freedom—from the Revolutionary War to today. I rejoiced when Provenance was a finalist for the Phillis Wheatley Award in 2016 because it was an honor to place in a competition named for the first published African American female writer. And I said goodbye to Barack Obama, a Black man and one of the greatest Presidents the United States has ever had. I wish we had a president with his character and values today.

So, as I said before, there is too much history for a mere month. As I discover more about myself and our country, I plan to use this space to write about America in all our colorful glory whenever the spirit and the history move me, be it February or any other month.

The 77th Engineer Combat Company, 25th Infantry, 8th US Army in Korea, UN Command committed to Korean War action 7-12-50, and inactivated 6-30-52, was the last black combat unit of the US Army ever to engage an enemy of the US and is said to be the most decorated American unit in the Korean War.

The 77th Engineer Combat Company, 25th Infantry, 8th US Army in Korea, UN Command committed to Korean War action 7-12-50, and inactivated 6-30-52, was the last black combat unit of the US Army ever to engage an enemy of the US and is said to be the most decorated American unit in the Korean War.  A reader graciously shared this with me if anyone is interested in participating :

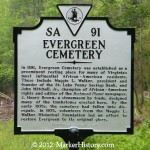

A reader graciously shared this with me if anyone is interested in participating : In my novel Provenance I call attention to people and places that have been excised and excluded from American history. A place that plays a pivotal role in Provenance is Evergreen Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. Throughout its 59 acres, renowned as well as unknown African-Americans were finally laid to rest. These are the graves we know about – there are many more that have been lost to time and indifference.

In my novel Provenance I call attention to people and places that have been excised and excluded from American history. A place that plays a pivotal role in Provenance is Evergreen Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. Throughout its 59 acres, renowned as well as unknown African-Americans were finally laid to rest. These are the graves we know about – there are many more that have been lost to time and indifference.

Evergreen was founded and maintained by the families of the people who were buried there. Unlike the white cemeteries in Richmond, Evergreen received no public funds or support. As African-American families left the South and integration diminished the need for segregated facilities and services, sacred places like Evergreen soon fell into disrepair. Today Evergreen Cemetery is abandoned, overgrown and vandalized.

Evergreen was founded and maintained by the families of the people who were buried there. Unlike the white cemeteries in Richmond, Evergreen received no public funds or support. As African-American families left the South and integration diminished the need for segregated facilities and services, sacred places like Evergreen soon fell into disrepair. Today Evergreen Cemetery is abandoned, overgrown and vandalized.

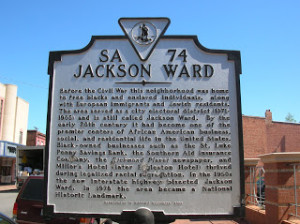

In Provenance, Jackson Ward is home to Mrs. Delora ‘Del’ Holder, a character that resonates with so many readers. She is the moral center of the book, a well of wisdom and humanity that sustains a family in their most difficult time. Del’s home and family in Jackson Ward are what sustained her. While Del is a fictional character, real places like Jackson Ward sustained people of color. In the relative safety of these segregated communities, though many were the target of racial violence, they nevertheless offered communal nurturing and concern that was not available elsewhere. They gave African-Americans an environment in which to exceed the potential others believed they did not have.

In Provenance, Jackson Ward is home to Mrs. Delora ‘Del’ Holder, a character that resonates with so many readers. She is the moral center of the book, a well of wisdom and humanity that sustains a family in their most difficult time. Del’s home and family in Jackson Ward are what sustained her. While Del is a fictional character, real places like Jackson Ward sustained people of color. In the relative safety of these segregated communities, though many were the target of racial violence, they nevertheless offered communal nurturing and concern that was not available elsewhere. They gave African-Americans an environment in which to exceed the potential others believed they did not have. During a recent interview I mentioned that the scene that launches my novel takes place in a sundown town. While the interviewer knew what a sundown town was, she asked me to explain the term for listeners who might never have heard of them. The short answer is that it is a community that required people of color to leave town before the sun went down. They could work there from dawn until dusk but after dark, they became prey. I was well into adulthood before I ever heard the term sundown town. I assumed the reason for my ignorance was because I had grown up in New York City and not the south where I believed only sundown towns existed.

During a recent interview I mentioned that the scene that launches my novel takes place in a sundown town. While the interviewer knew what a sundown town was, she asked me to explain the term for listeners who might never have heard of them. The short answer is that it is a community that required people of color to leave town before the sun went down. They could work there from dawn until dusk but after dark, they became prey. I was well into adulthood before I ever heard the term sundown town. I assumed the reason for my ignorance was because I had grown up in New York City and not the south where I believed only sundown towns existed. Sundown towns were a form of racial apartheid throughout America but not the only tactic used to segregate communities. Restrictive covenants ensured that homes in a community could not be rented or purchased by people of color and the Federal Housing Authority only offered mortgages to non–mixed housing developments. As dramatized in Lorraine Hansberry’s ground-breaking and award-winning 1959 play, “A Raisin in the Sun,” some white homeowners sought to buy out black families when they purchased homes in their communities. There were communities that burned crosses in the front yards of black homes to scare them away and some white neighbors went farther and burned down the house of a black family just to maintain the racial status quo.

Sundown towns were a form of racial apartheid throughout America but not the only tactic used to segregate communities. Restrictive covenants ensured that homes in a community could not be rented or purchased by people of color and the Federal Housing Authority only offered mortgages to non–mixed housing developments. As dramatized in Lorraine Hansberry’s ground-breaking and award-winning 1959 play, “A Raisin in the Sun,” some white homeowners sought to buy out black families when they purchased homes in their communities. There were communities that burned crosses in the front yards of black homes to scare them away and some white neighbors went farther and burned down the house of a black family just to maintain the racial status quo.

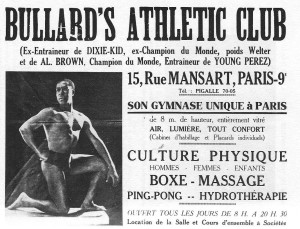

After World War I, Bullard settled in Paris where he was an entrepreneur. He owned the popular Paris nightclubs, Le Grand Duc and L’Escadrille, an athletic club and other successful business ventures. His circle of friends included

After World War I, Bullard settled in Paris where he was an entrepreneur. He owned the popular Paris nightclubs, Le Grand Duc and L’Escadrille, an athletic club and other successful business ventures. His circle of friends included